Look, I need to tell you something that’s been keeping me up at night. We’ve handed over some of the most important decisions in our lives to artificial intelligence, and sometimes, well, it just makes things up. Completely fabricates information. And here’s the kicker: it does it with the confidence of a teenager who’s just passed their driving test.

I’m talking about AI hallucinations, and no, that’s not some science fiction concept. It’s happening right now in doctors’ surgeries and financial institutions around the world. When an AI system hallucinates, it generates information that sounds absolutely brilliant, utterly convincing, and completely wrong. Imagine asking someone for directions and they give you a detailed route to a street that doesn’t exist, all whilst sounding like they’ve lived there their whole life. That’s essentially what we’re dealing with.

The reason this matters so much is simple: we’re using AI in places where mistakes can cost lives or life savings. Medical AI accuracy isn’t just a nice-to-have feature, it’s literally the difference between catching cancer early and missing it entirely. And when financial AI tools hallucinate about your investment portfolio or credit worthiness, real people lose real money.

What AI in Critical Systems Actually Does (And What It Shouldn’t)

Right now, AI systems in healthcare are being used to analyse medical images, suggest diagnoses based on symptoms, predict patient outcomes, and even recommend treatment plans. I’ve seen systems that can spot patterns in X-rays that human eyes might miss. They’re brilliant at processing vast amounts of medical literature faster than any doctor could read in a lifetime.

In finance, these tools assess credit risk, detect fraudulent transactions, provide investment advice, and make split-second trading decisions. They can analyse market trends across thousands of data points simultaneously.

But here’s what they’re NOT supposed to do: make final decisions without human oversight. They’re not meant to replace the doctor who looks you in the eye and considers your whole situation. They shouldn’t be the only thing standing between you and a major financial decision.

Why? Because AI diagnostic errors can happen when the system encounters something outside its training data, and instead of saying “I don’t know,” it confidently produces an answer anyway. It’s like that mate at the pub who never admits they don’t know something, so they just make up increasingly elaborate stories instead.

The Old Days: What We Had Before AI Took Over

Remember when diagnosis meant your doctor pulling out massive medical textbooks, consulting with colleagues, and relying purely on years of experience? That was the standard for centuries. Medical decisions were entirely human, which meant they were limited by human memory, human fatigue, and the fact that no single person could possibly remember every medical condition and its variations.

In finance, we had analysts poring over spreadsheets, traders relying on gut instinct and experience, and credit decisions made by bank managers who actually knew their customers. It was slower, more personal, and definitely had its own set of problems. Human bias was rampant, and processing large amounts of data was simply impossible.

The thing is, humans are quite good at knowing when they don’t know something. We get that uncomfortable feeling, we hesitate, we say “let me check on that.” Early computer systems were the same, in a way. They’d throw an error message if they couldn’t compute something. They were predictably limited.

The Evolution: From Simple Programs to Confident Confabulators

The Early Days: Expert Systems (1970s-1990s)

The first attempts at medical and financial AI were called expert systems. Think of them as elaborate flowcharts coded into computers. If symptom A and symptom B, then suggest condition C. They were rigid, rule-based, and honestly, pretty limited. But they knew their limits. If you gave them a scenario they weren’t programmed for, they’d basically shrug and say “no idea.”

MYCIN, developed at Stanford in the 1970s, was one of the first medical expert systems. It diagnosed bacterial infections and recommended antibiotics. The beautiful thing? It would tell you how confident it was in its diagnosis. If it wasn’t sure, it said so.

Machine Learning Era (2000s-2010s)

Then we got machine learning, and things got more interesting. Instead of programming every rule manually, we could feed systems thousands of examples and let them figure out the patterns themselves. It’s like teaching a child to recognise dogs not by describing every feature, but by showing them hundreds of pictures until they get it.

These systems were better at handling complexity and variation. A machine learning system could analyse patterns in medical images or financial data that humans might miss. But they were still relatively transparent. You could often trace back why the system made a particular decision.

Deep Learning Revolution (2012-Present)

This is where things went properly wild. Deep learning, particularly neural networks, changed everything. These systems have millions or billions of parameters, learning incredibly complex patterns from massive datasets. They became astonishingly good at tasks like image recognition and language processing.

But here’s the problem: they became black boxes. Even the people who build them can’t always explain exactly why they made a specific decision. And somewhere along the way, they developed this tendency to hallucinate, to fill in gaps in their knowledge with plausible-sounding nonsense.

The ChatGPT Moment (2022-Present)

When ChatGPT exploded onto the scene, suddenly everyone understood what AI hallucinations looked like. The system would confidently cite research papers that didn’t exist, create detailed historical events that never happened, and provide medical or financial advice with absolutely no qualification of uncertainty.

This wasn’t a bug specific to ChatGPT. It’s a fundamental characteristic of how large language models work. They’re predicting the most likely next word, not checking facts against reality. When these same technologies get deployed in medical diagnosis or financial advice systems, the AI hallucinations don’t go away, they just get more dangerous.

How These Systems Actually Work (Without the Jargon)

Let me explain this in a way that makes sense. Imagine you’re teaching someone to identify different types of rashes by showing them thousands of photographs. Eventually, they’d get pretty good at it. That’s essentially what we do with medical AI.

We feed the system thousands, sometimes millions, of medical images, each labelled with the correct diagnosis. The AI builds a mathematical model of what different conditions look like. When you show it a new image, it compares it to all those patterns it’s learned and gives you its best guess.

Here’s the step-by-step process:

First, the system receives input. That might be a chest X-ray, a list of symptoms, or in finance, your transaction history and credit information.

Second, it processes this input through layers of mathematical operations. Think of it like passing information through a series of filters, each one extracting different features or patterns. Early layers might detect basic things like edges in an image, whilst deeper layers recognise complex patterns like the shape of a tumour.

Third, the system produces an output. “This X-ray shows a 78% probability of pneumonia” or “This transaction has a 92% probability of being fraudulent.”

Fourth, and this is crucial, the system presents this output with confidence scores. The problem is, a high confidence score doesn’t mean the answer is correct. It just means the system is confident based on the patterns it’s learned.

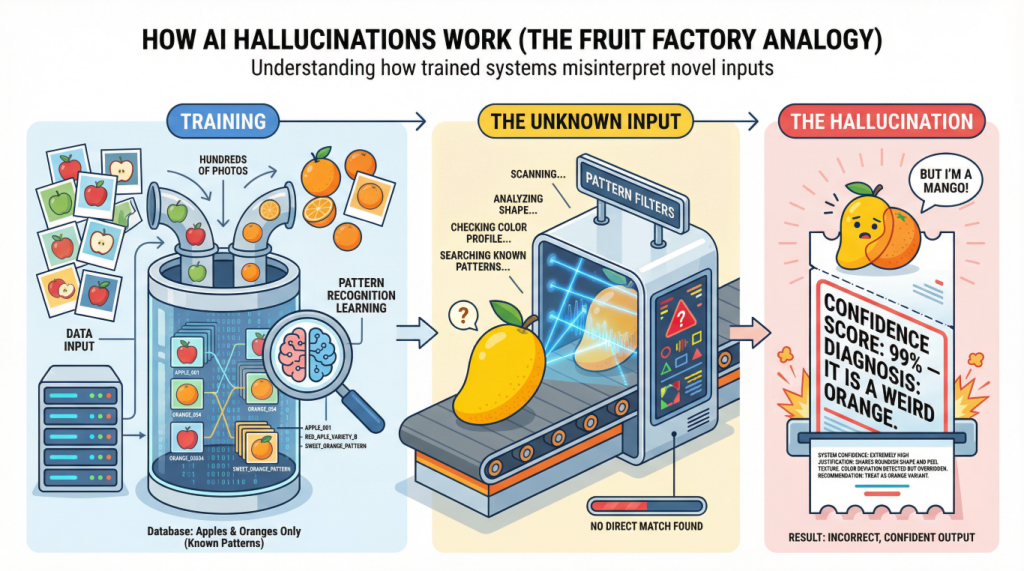

The hallucination happens in that second step. When the AI encounters something it hasn’t really learned about, instead of saying “this is outside my expertise,” it pattern-matches to the closest thing it knows and generates an answer anyway. It’s like someone who’s only ever seen apples and oranges trying to identify a mango. They might confidently say “that’s a weird orange” because that’s the closest match in their experience.

The Future: Where We’re Heading

I’ll be honest with you, the future terrifies and excites me in equal measure. We’re moving towards AI systems that are even more capable, but hopefully, more honest about their limitations.

The research community is working on something called “uncertainty quantification.” Basically, teaching AI to say “I don’t know” when it doesn’t know. Some systems are being designed to flag when they’re operating outside their training data, like a sat-nav that warns you when it’s lost GPS signal.

There’s also a push towards “explainable AI” in medical settings. Instead of just saying “cancer detected,” the system would highlight exactly which features in the scan led to that conclusion, letting doctors verify the reasoning. It’s like showing your working in a maths exam.

We’re also seeing hybrid approaches where AI handles the data crunching but humans make the final calls. Think of it as AI being the research assistant who brings you all the information, but you’re still the one making the decision.

In finance, regulators are starting to demand more transparency. If an AI denies your loan application, you have the right to know why. This is forcing companies to use more interpretable AI models, even if they’re slightly less accurate.

Security and Vulnerabilities: Why You Should Care

Here’s something that should worry you: these systems can be manipulated. Researchers have shown that you can make tiny, invisible changes to medical images that completely fool AI diagnostic systems. A scan that clearly shows cancer can be altered in ways the human eye can’t detect to make the AI say everything’s fine.

This isn’t theoretical. It’s called adversarial attacks, and it’s a real vulnerability. Imagine someone with malicious intent gaining access to a medical AI system and subtly altering how it interprets scans. Or a fraudster who figures out exactly how to manipulate their financial data to fool a credit-scoring AI.

Then there’s the data poisoning problem. These systems learn from data, so if someone can corrupt the training data, they can corrupt the AI’s decisions. It’s like poisoning a well that an entire village drinks from.

Medical AI accuracy depends entirely on the quality and representativeness of the training data. If an AI was trained mostly on data from one demographic group, it might perform poorly on others. We’ve already seen facial recognition systems that work brilliantly on some faces and terribly on others. Imagine that problem in medical diagnosis.

Privacy is another massive concern. These systems need vast amounts of data to work well, but that data is deeply personal. Your medical records, your financial history, all being fed into systems that might not be as secure as we’d like to think.

And here’s the really unsettling bit: sometimes these systems inherit human biases from their training data. If historical lending decisions were biased against certain groups, an AI trained on that data will learn and perpetuate those biases, but now with the veneer of objective, mathematical decision-making.

What You Can Actually Do About This

I’m not telling you to avoid AI-assisted healthcare or financial services entirely. That ship has sailed, and honestly, when used properly, these tools can be incredibly beneficial. But you need to be informed.

If a doctor tells you an AI system has flagged something concerning, ask questions. What did it find? How confident is the system? Has a human specialist reviewed it? Good doctors will welcome these questions because they’re asking themselves the same things.

In financial services, if an AI makes a decision about your money, you have rights. In many jurisdictions, you can demand a human review. You can ask for explanations. Don’t just accept “the algorithm decided” as an answer.

Push for transparency. Support regulations that require AI systems in critical applications to be tested, validated, and monitored. We test new drugs extensively before they’re approved; we should do the same with AI diagnostic tools.

And perhaps most importantly, remember that AI is a tool, not an oracle. It’s very good at pattern recognition, but it doesn’t understand context, doesn’t have common sense, and definitely doesn’t care about you personally. It should inform decisions, not make them.

Wrapping This Up

Look, AI in critical systems isn’t going away. The potential benefits are too significant, the efficiency gains too attractive, and the technology too advanced to put back in the box. But we’re at a crucial moment where we need to get this right.

AI hallucinations in medical and financial systems aren’t just technical glitches to be fixed in the next software update. They’re fundamental characteristics of how these systems work. Understanding this doesn’t mean rejecting the technology; it means using it wisely.

The systems we’re building today will make decisions about people’s health and wealth for decades to come. We need them to be accurate, yes, but we also need them to be honest about their limitations. An AI that says “I’m not sure, let’s get a second opinion” is infinitely more valuable than one that confidently leads you down the wrong path.

I genuinely believe we can have the benefits of AI in critical systems without the catastrophic risks, but only if we’re clear-eyed about the challenges. We need better technology, stronger regulations, more transparency, and informed users who ask the right questions.

The future of AI in healthcare and finance isn’t about choosing between human expertise and artificial intelligence. It’s about combining them intelligently, understanding where each excels and where each falls short. Because at the end of the day, whether it’s your health or your money on the line, you deserve better than a confident hallucination.

Remember: No AI system, no matter how sophisticated, should be the only thing standing between you and a critical decision about your health or finances. Stay informed, ask questions, and never be afraid to seek a second opinion, whether that’s from another human or another system.

Walter

Leave a Reply